MEV: Blockchain’s Silent Assassin:

Delving into Miner Extractable Value (MEV) through Exploratory Research connecting to machine learning

Disclaimer: This article is a final deliverable from Prof. Luyao Zhang’s project entitled “From ‘Code is Law’ to ‘Code and Law’: A Comparative Study on Blockchain Governance,” supported by the 2023 Summer Research Scholarship (SRS) program at Duke Kunshan University. Our Summer 2023 scholars also receive additional support from Wang-Cai Biochemistry Lab Donation Fund. SciEcon wholeheartedly supports DKU’s noble mission of advancing interdisciplinary research and fostering integrated talents. Our support is solely focused on promoting academic excellence and knowledge exchange. SciEcon does not seek any financial gains, property rights, or branding privileges from DKU. Moreover, individuals involved in this philanthropy event perform their roles independently at DKU and SciEcon.

Keywords: #MEV #Cryptocurrency #Machine Learning #DeFi Highlights: * Research: Research existing machine learning methods for detecting MEV in Ethereum, helping solve one of the most significant ethical problems in the blockchain. * Innovation: Identify limitations to the current methodology applied to detect MEV. * Leadership: Provide future research directions for detecting MEV using machine learning.

Introduction

Miner Extractable Value (MEV) has garnered significant attention from researchers due to its implications for the security and privacy of blockchain networks. Mainly, MEV is unethical due to its exploitation of vulnerabilities. MEVs can exploit vulnerabilities in smart contracts or decentralized protocols, taking advantage of flaws or weaknesses in their design (Qin, Zhou, and Gervais, 2022), which leads to unfair advantages for those with knowledge of these vulnerabilities, potentially resulting in financial harm to other participants. Consequently, the dark forest has led to distrust in blockchain transactions. The current cryptocurrency market needs help solving and detecting the MEV promptly, and the problem has become one of the most significant issues on Ethereum. According to Flashbots, MEV has extracted over $600 million in only two years, and the number is continuously increasing.

Figure 1. Total MEV on the Ethereum network from 2020 to 2022

Figure 1 illustrates that within three years, the cumulative gross profit of MEV has reached $673M recently, which increased extremely quickly during 2021. Still, perhaps due to more countermeasures coming out in recent years, its growth is slowing recently.

What is MEV?

MEV refers to the potential profits that miners can extract from the order of transactions within a blockchain. It arises from the unique structure of blockchain networks, where miners can prioritize and include specific transactions in a block. By manipulating the order of transactions, miners can potentially exploit market conditions to their advantage and extract additional value from the network (“Miner Extractable Value (MEV),” n.d.). MEV can result in various outcomes, including front-running, where miners profit by executing transactions before others, and arbitrage opportunities. While MEV can offer financial benefits to miners, it has also raised concerns about fairness, transparency, and the overall integrity of decentralized systems.

How can MEV be implemented and applied?

MEV can be implemented and applied in various ways within blockchain networks, mainly distributed into three categories.

1. Arbitrage Opportunities

MEV can arise from price discrepancies or imbalances across decentralized exchanges or trading platforms. Miners can identify these opportunities and exploit them by executing trades to capitalize on price differentials. Such arbitrage action often occurs when the token prices differ on diverse, decentralized exchanges (DEX)[2]. The miner buys the token on the cheaper DEX and sells it immediately on the other DEX to make a profit (Park et al. 2023).

An example of an arbitrage attack bot is demonstrated by an incident involving an attacker who used a bot to exploit the Polygon network. According to Adejumo (2021), the bot inflated transaction volumes by 90% over four months using meaningless transactions, taking advantage of low network fees. By paying a small fee of 0.02 MATIC per transaction block, the bot earned roughly $1000 per day. Further investigation revealed that two arbitrage bots were responsible for nearly 30% of all transactions on Polygon. The attacker turned 14 ETH into 218.5 ETH, resulting in a daily profit of approximately $7000. The increase in Polygon’s gas fees is believed to be connected to the activities of this spammer, as the team sought to address the system manipulation. The higher fees have since led to a significant decrease in the transactions on Polygon.

2. Sandwich Attack

A sandwich attack involves the insertion of a malicious transaction by a miner between two legitimate transactions to exploit price movements or take advantage of pending transactions. In a sandwich attack, the malicious miner carefully monitors pending transactions within the network (Züst et al. 2021). They look for specific transaction patterns or predictable behaviors to exploit for financial gain. Once identified, the miner quickly inserts their transaction between the two target transactions, forming a “sandwich.” The purpose of this sandwich is to manipulate the market conditions in favor of the attacker. By executing their transaction at the opportune moment, the malicious miner can profit from price discrepancies or exploit the predictable outcomes of the surrounding transactions. This can lead to unfair advantages, front-running, and potential financial losses for other participants in the network. Sandwich attacks can be particularly effective in decentralized exchanges or automated market makers where trading occurs based on predetermined algorithms or smart contracts. The malicious miner leverages their knowledge of pending transactions and market conditions to execute trades and maximize their profits strategically.

From another report by Adejumo (2023), on April 18th, 2023, an MEV bot spent about 7% of total gas on Ethereum in 24 hours, worth over $1M. Most bot transactions are sandwich attacks targeting traders trading low-cap tokens like PEPE, BONZI, and WOJAK.

3. Liquidation

Liquidation occurs when the value of the collateral falls below a threshold, and MEV can impact this process in several ways. Miners can engage in “liquidation sniping” by prioritizing their transactions to liquidate undercollateralized positions before others, allowing them to profit from the liquidation event (“Liquidations-FAQ” 2023). Additionally, miners can reorder liquidations, potentially manipulating the order to their advantage and extracting additional value. They can also exploit timing discrepancies and perform transactions that interact with liquidations in ways that benefit them financially. These MEV-driven liquidation strategies raise concerns about fairness, transparency, and stability in DeFi. Efforts are being made to address these issues through improved mechanisms, better transaction ordering, and fee optimization techniques to create a more secure and equitable DeFi ecosystem.

From research by Garg (2020), on March 12th, 2020, BitMEX, one of the largest cryptocurrency exchanges in the world, suffered a 25-minute outage, making the price of Bitcoin super low and causing $1.2B long contracts to be liquidated. The BitMEX became a victim of a liquidation attack, and the outage allowed some selfish miners significant profits.

Detection

The basic logic of MEV detection involves analyzing transaction data and smart contract interactions to identify patterns and behaviors indicative of MEV activities. For example, detecting MEV in centralized Application Programming Interface (API) services using ABI (Application Binary Interface) involves analyzing the interaction between smart contracts and the Ethereum blockchain. By examining the sequence and content of transactions and their associated ABIs, it is possible to identify potential MEV behaviors. According to Piet, Fairoze, and Weaver (2022), Flashbots, and Qin, Zhou, and Gervais (2022), one general process typically includes the following steps:

1. Importance of Centralized API Services:

According to the research (“API Platforms: Centralized vs. Decentralized,” n.d.), centralized API services act as intermediaries between users and the Ethereum blockchain. They provide simplified access to blockchain data and functionality, making it easier for developers to interact with smart contracts and retrieve information. MEV detection within these centralized services helps identify and prevent potential harmful actions. For instance, Etherscan allows users to explore individual transactions on the Ethereum network (Park et al. 2023). By examining transaction details, gas prices, and timestamps, users can identify potential signs of MEV, such as frontrunning or other transaction ordering strategies.

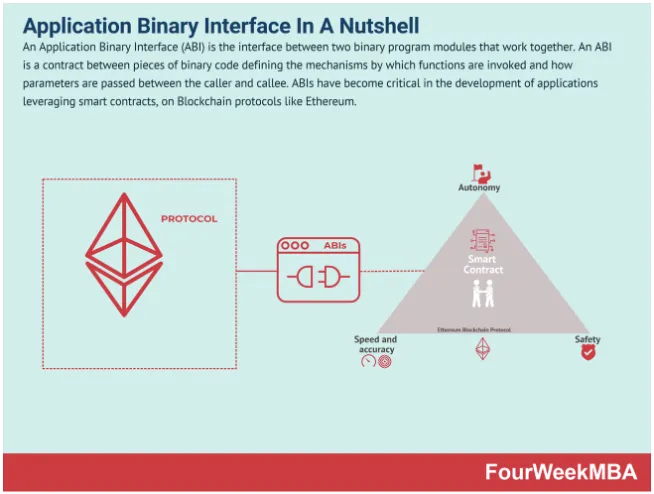

2. Application Binary Interface (ABI):

ABI defines how smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain communicate with each other and external services. It specifies the structure and encoding of function calls and contract interactions. By leveraging the ABI, it becomes possible to analyze the content and parameters of transactions, gaining insights into the intentions and behaviors of contract interactions.

Figure 2. Application Binary Interface

Figure 2. Application Binary Interface

Basic Logic of MEV Detection:

The basic logic of MEV detection in centralized API services using ABI involves the following steps:

1. Transaction Retrieval:

Centralized API services retrieve transaction data from the Ethereum blockchain. This includes transaction hashes, sender and recipient addresses, gas prices, and block numbers.

2. Contract Interaction Analysis:

The ABI of the involved contracts is used to decode the input data of each transaction. This allows for identifying function calls and parameters passed during contract interactions.

3. MEV Signature Detection

MEV signatures refer to specific function calls or parameter combinations that indicate potential MEV behaviors. Defining a set of known MEV signatures makes it possible to match them against the decoded transaction data. If a match is found, it suggests the presence of MEV activities.

4. MEV Behavior Classification:

Detected MEV signatures can be categorized into different MEV behaviors, such as front-running, sandwich attacks, or miner-prioritized transactions. This classification provides insights into the specific MEV strategies employed.

5. Alert Generation:

When potential MEV behaviors are identified, alerts or notifications are generated within the centralized API service. These alerts can be sent to users, developers, or platform administrators to raise awareness about the detected MEV activities.

Figure 3. Basic MEV detection process (created by Whimsical)

Figure 3. Basic MEV detection process (created by Whimsical)

Figure 3 shows a user's basic process for getting transaction data from Ethereum. The user will send the registration code to some centralized API services, like Etherscan, which stores ABI to decode and allow us access to the transaction data. After preprocessing the transaction data, we can use start to detect MEV.

Case Study

Use Machine Learning to detect MEV

Front-running involves miners executing transactions ahead of others to exploit price movements. Machine learning algorithms can be trained to analyze transaction data, order timestamps, and price changes to identify patterns indicative of front-running behavior. By learning from labeled data representing known instances of front-running, the algorithm can recognize similar patterns in real-time transactions and raise alerts.

Simultaneously, labeled data that represent known instances of sandwich attacks are used for training the model. Weintraub et. al. (2022) and Flashbots have provided us with tools to label potential MEV transactions. The model learns the transaction patterns associated with sandwich attacks, including the specific positioning of the malicious transaction. Real-time transaction data can be evaluated against these learned patterns to detect potential sandwich attacks.

Figure 4. Labelled MEV vs Flashbots

Figure 4. Labelled MEV vs Flashbots

Figure 3: its x-axis marks the number of blocks, while its y-axis shows the number of detected MEV transactions. The yellow line was drawn by Park et al. (2023) using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to label MEV, and the blue one was drawn by using Flashbots-inspect. The figure tells that GNNs have successfully detected much more MEV than Flashbots. GNNs can learn different patterns without specifying the category of potential MEV.

Limitation and Future Research Direction

The current detection methods of MEV are challenging in solving computational issues, identifying practical features, and capturing temporal dynamics.

First, both data processing and machine learning are facing computational issues. One challenge is the scarcity of labeled training data specifically for MEV-related attacks. Collecting a comprehensive dataset of labeled examples for different MEV strategies can take time, limiting the accuracy and generalizability of the models. To give an example of the computational issues, GNNs can face scalability issues when dealing with large-scale transaction graphs, especially in scenarios where the number of nodes and edges is substantial. Training GNNs on such graphs can be computationally expensive and time-consuming. Efficient techniques like graph sampling or graph pooling may be necessary to handle the computational complexity and make GNNs more scalable. Simultaneously, for some specific machine learning methods, Support Vector Machines (Pisner and Schnyer, 2020) and logistic Regression(Hosmer, 2000) rely on the input features provided for classification.

Second, In MEV detection, designing practical features that capture the nuances of MEV behavior can be challenging. The success of these models heavily depends on the quality and relevance of the chosen features. Considering arbitrage attack merely, it has many subcategories with different features, adding great difficulty to detect all kinds of MEV. Additionally, neural networks (Maddipati Varun, Balaji Palanisamy, and Shamik Sural, 2022) have primarily focused on meta-transaction data, such as gas prices. This approach may not fully capture the graph structure of token transfers during transaction execution, potentially limiting the model’s performance.

Third, MEV detection often requires capturing transactions' temporal dynamics and ordering. For future research, sequence modeling techniques, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) (Grossberg, 2013), can be used to capture dependencies and patterns in transaction sequences. These models can learn the sequential transaction relationships and identify MEV-related sequences. The new machine learning methods must learn different MEV features and label the data accurately. Also, accessing transaction data still needs to be fixed. Due to limitations in accessible ABI, some MEV characterizations cannot be confirmed and labeled.

Finally, MEV strategies can evolve and adapt over time to avoid detection. To remain effective, machine learning models must continually update and adapt to new MEV techniques. Adversarial strategies can also deliberately bypass detection methods, requiring constant vigilance and model refinement.

Relevant Materials

[1] Flashbots

Flashbots is a unique and specialized system designed to address the issue of MEV on Ethereum. It aims to mitigate MEV’s effect and provide a more fair and transparent mechanism for capturing value from transaction execution while minimizing the adverse effects of MEV. It offers a way for users to interact directly with miners, enabling them to achieve desired outcomes without the risk of front-running or transaction reordering.

[2] Decentralized exchange (DEX)

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) are platforms that facilitate the peer-to-peer trading of cryptocurrencies and tokens, requiring no need for intermediaries or centralized authorities. They operate on blockchain networks, such as Ethereum, and provide users with control over their funds and the ability to trade directly with other participants.

[“What Are Decentralized Exchanges, and How Do DEXs Work?,” n.d.]

About the Author

Jiayi Wang

Figure 5. Jiayi Wang

Figure 5. Jiayi Wang

Jiayi Wang is a junior student at Duke Kunshan University majoring in Applied Math & Computational Science tracking in Math. He has a solid foundation in Data Science and excels in Math. He has researched trading strategies and portfolio construction in the Chinese Commodity Market. He is working under the guidance of Prof. Luyao Zhang on machine learning for Blockchain Security and Privacy.

Acknowledgments

Interim Executive Editors: Xintong Wu, Wanlin Deng

Associate Editor: Xinyu Tian

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang

Design: Yixuan Li