Are Central Banks Digital Currencies (CBDCs) The Future of Money?

SciEcon AMA Interview with Luciano Somoza

On October 1st, 2021, SciEcon AMA member Francesco Cavallero interviewed Ph.D. candidate Luciano Somoza at the Swiss Finance Institute and at HEC Lausanne — University of Lausanne.

About Luciano Somoza

Figure 1: Luciano Somoza

Luciano Somoza is a Ph.D. candidate in economics with a specialization in finance at the Swiss Finance Institute and at HEC Lausanne — University of Lausanne. He is also an adjunct teacher at the University of Luxembourg. His research interests include banking, financial regulation, and fintech. His works have been featured in the Financial Times, Il Sole 24 Ore, LSE Business Review, and Oxford Business Law Blog. He received an M.Sc. in finance from the University of Rochester in 2016 and a B.A. in economics and finance from Bocconi University in 2014.

Read the Interview Script with annotation and graphs.

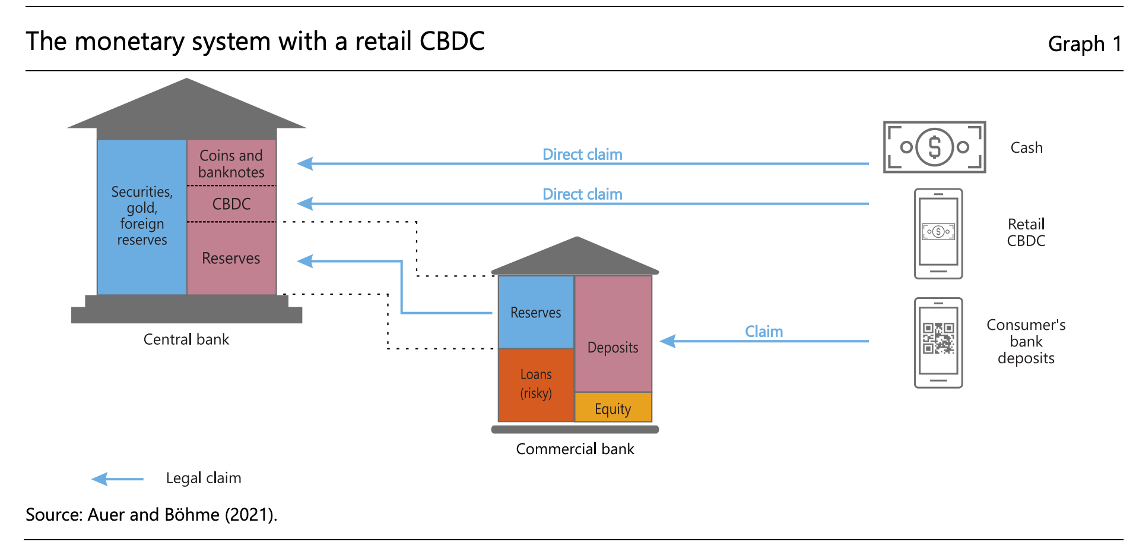

Figure 2: Introduction to retail CBDC vs other payment methods. Source: BIS

Question 1

Francesco:

What is the biggest change Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) can bring to the financial system as well as the global economy?

Luciano:

Unlike what people may mistakenly think, CBDCs are not only about technology. Yes, they have the potential to speed up payment systems, cut transaction costs, and improve financial inclusion, but it’s more than meets the eye. CBDCs are designed to bring a radical change in how money works. Today, you can either pay by cash or credit card. Cash is essentially a liability of a country’s central bank, which acts as a guarantor of a transaction between two parties. On the other hand, whenever individuals pay with credit cards, they are transacting bank credits, which are denominated in a domestic or international currency, such as the dollar. However, bank credits are not dollars because if a bank goes bankrupt, bank credits are worth nothing to its depositors. Similarly, banks normally have an account at a country’s central bank, where they settle transactions with other banks at the end of each day. This is how our global payment system works today. The future of payments will likely be different from what we have been used to in the past. Governments and central banks around the world are thinking of allowing everybody to open a deposit account at the central bank. In other words, if you go to Walmart and pay for your groceries, you are exchanging a central bank’s liability, not a bank’s. This may have marginal implications for the end customer, other than being a slightly cheaper, faster means of payment, but it has great implications for everything that happens behind the curtains. For example, if a bank’s depositor wants to transfer her money to a newly opened bank account at the central bank, it is worth understanding how the transfer will take place between the two banks. It raises important questions like:

- Should the central bank compensate commercial banks for the loss of deposits?

- Should we be worried about disintermediation?

- Who is going to distribute the digital currency?

- Is the central bank collecting transaction data? (today central banks do not have access to granular payment data)

- Who’s collecting transaction data that are currently not available to central banks on a granular level?

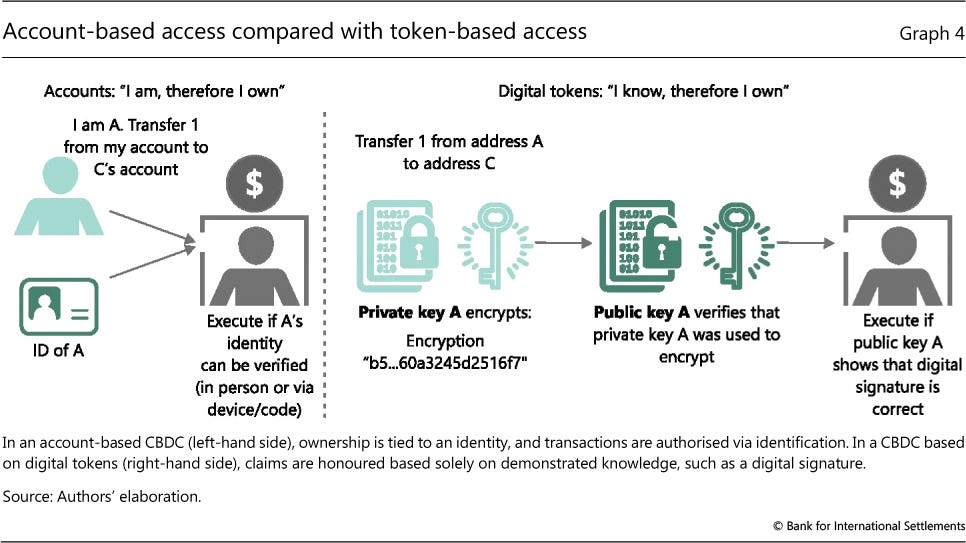

In terms of how CBDCs will be designed, there is a fundamental choice to make: a token-based or an account-based CBDC. With a token-based CBDC, a payment’s receiver verifies the authenticity of the token, just like with physical banknotes. An account-based CBDC would resemble a normal bank deposit. Either way, central banks will likely set in the beginning a maximum limit on the amount of digital currency in your e-wallet, thus restricting its use to small transactions.

Figure 3: Account-based vs Token-based CBDC. Source: BIS

Question 2

Francesco:

An external observer may feel overwhelmed by the number of emerging technologies that are redefining the global financial system. So, what do you envision to be the future of money?

Luciano:

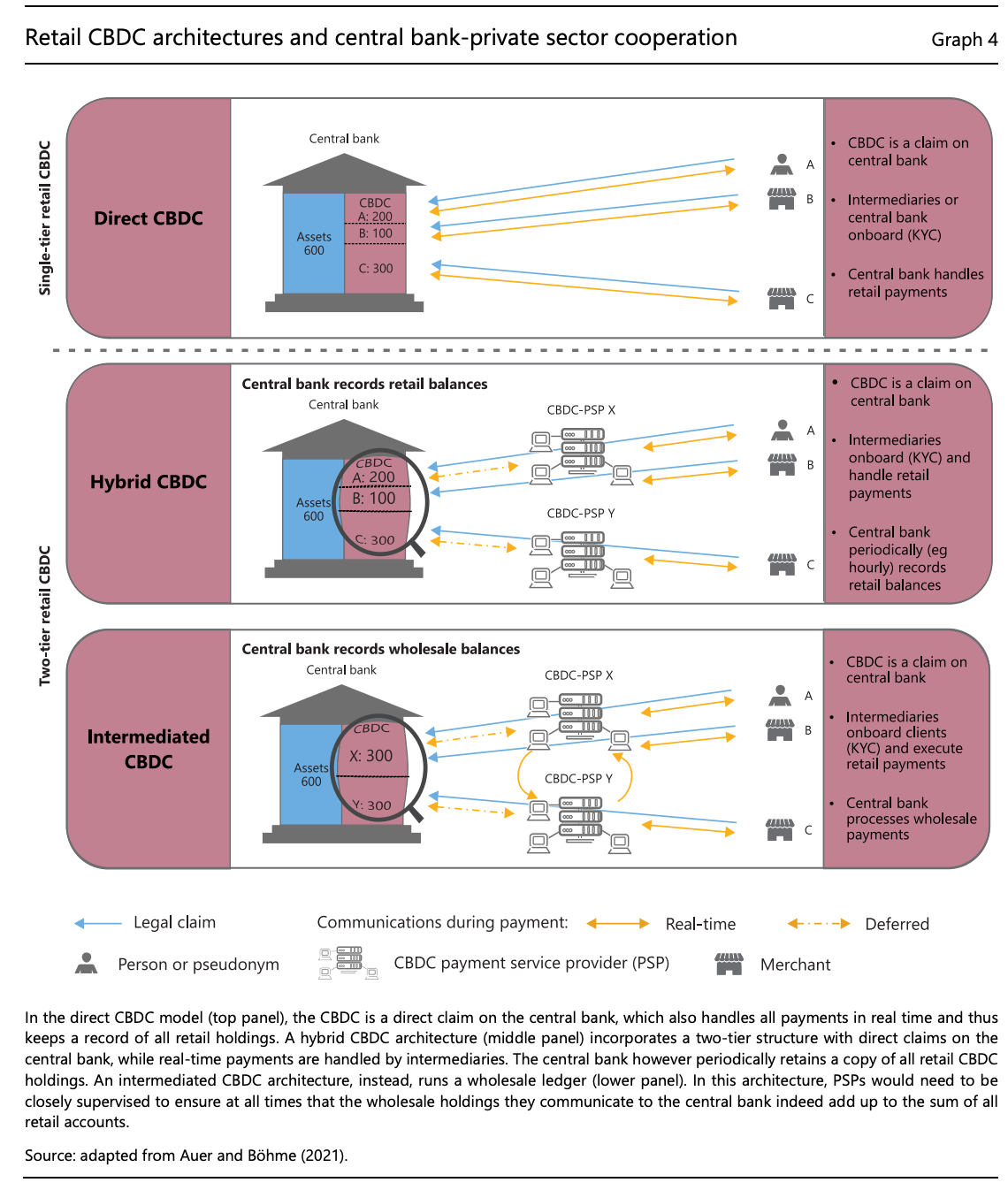

Politics will be exceptionally crucial in determining what the future of money in 2030 might look like. My best guess is that CBDCs will likely establish themselves as the most widely used means of payment in the next 15 to 20 years. Whether CBDCs will be token-based or account-based is still to be determined, but it would not be surprising to see a hybrid CBDC design being implemented. Governments must also address questions about the distribution channels of their own CBDC. Will CBDCs be distributed directly by central banks, crowding out commercial bank deposits? Or, will central banks pass the funds through the commercial banks, which will act as intermediaries of the CBDC? Although central banks around the world are currently exploring both options, CBDCs are most likely to be distributed by commercial banks, leaving the environment for banks unchanged.

Traditional private cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, are not money since they are not used for payments. Instead, individuals tend to use Bitcoin for speculative, hedging, and diversification purposes. Evidence from a financial firm’s proprietary data shows that there exists a strong substitution effect between some speculative assets and bitcoin. In some developing countries with high inflation rates, however, private cryptocurrencies can represent an attractive alternative to fiat money or cards.

Stablecoins, on the other hand, might play an important role, but there is a risk associated with government intervention. This was the case, for example, in China, where the government has imposed a 100 percent reserve requirement to Alipay, meaning that every time a customer converts some Chinese yuan into Alipay money, the firm must deposit the same amount in the central bank. In other words, Alipay is a synthetic CBDC because it is 100 percent backed by the central bank. You just have an intermediary in the middle who is taking care of the payment technology. This was done out of political considerations. One might agree or disagree, but whenever you have powerful intermediaries in an economy, regulators often start getting worried about their role. The same happened with Libra in the US, where the government was reluctant to allow Facebook to pursue monetary experiments. Therefore, regulators will most likely step in whenever a private means of payment becomes too influential by either imposing stricter regulation or by issuing their own CBDC.

Figure 4: Retail CBDC design. Source: BIS

Question 3

Francesco:

We read your article published in the Financial Times-Alphaville titled “CBDCs must be coupled with greater accountability.” In this article, you focused on the influences of CBDC on the balance sheets of the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve. Can you summarize the pros and cons of introducing CBDCs for different stakeholders, such as central banks, commercial banks, and individuals?

Luciano:

From a consumer’s perspective, the advantages of CBDCs are quite marginal. Domestic and cross-border transactions might be cheaper and faster. It might also be easier for merchants to offer different virtual transactions. On the other hand, the introduction of CBDCs will have a larger impact on commercial banks, which might see a decrease in the number of deposits. If commercial banks do lose deposits, then it will become much harder for them to offer complementary financial services, and they could no longer draw on deposits as their main source of funding. Central banks can potentially address this problem by collecting deposits and funding commercial banks directly. Under such a scenario, commercial banks would still be able to retain all customer data, provide complementary services, and attract new customers. Ultimately, central banks will be the ones who will experience the biggest change from the introduction of a CBDC since they will have retailers in their balance sheet, regardless of whether CBDCs will be distributed through them or via banks. A direct channel between central banks and retailers will result in more targeted monetary policies at the expense of customers’ privacy. Furthermore, part of what my research has been focusing on, introducing a CBDC under quantitative easing programs may have profound consequences on a central bank’s ability to reverse its expansionary monetary policies. When commercial banks use their excess reserves to allow depositors to convert bank deposits into CBDC deposits, retailers become the new creditors of the central bank. Then, it might be more difficult — yet not impossible — to convince retailers to give back their deposits when a central bank is determined to taper its balance sheet. So, tapering a balance sheet when liabilities are in the hand of retailers is much harder, rendering QE program quasi-permanent eventually.

Figure 5: ECB and Fed’s balance sheets from 2006 to 2022. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Question 4

Francesco:

How will a CBDC affect the effectiveness of monetary policy during the period of a financial crisis? Will CBDC deteriorate or mitigate inflation?

Luciano:

In terms of the effectiveness of monetary policy in times of financial crises, central banks can benefit from CBDCs because they will be able to implement more targeted monetary policies, by directly affecting households’ deposits. This might facilitate the integration of fiscal and monetary policies, thus blurring the line between the responsibilities of the central bank and those of the fiscal authorities. Also, you might see central banks trying to do much more precise targeting of inflation because the instrument is much better at micromanaging monetary policies. On the other hand, the problem may arise in the long-term where people will start to think that central banks have monetary superpowers and can print money indefinitely, resulting in changes in inflation expectation. As you can imagine, it becomes very difficult to predict the general equilibrium effect of CBDCs on inflation.

The question that policymakers ought to be asked is: “Do the benefits of introducing a CBDC outweigh the costs? And is the risk worth taking?” In my opinion — which is not reflected in my research — the risks of introducing a CBDC are enormous. When assessing the risks associated with this technology, central bankers should consider the effects in 20 or 30 years, regardless of whether CBDCs will be used only for payments or other more sophisticated purposes.

Figure 6: Timeline of CBDC projects. Source: BIS

Acknowledgments:

Interviewee: Luciano Somoza

Interviewer: Francesco Cavallero

Executive Editor: Ray Zhu, Xinyu Tian

Chief Editor: Prof. Luyao Zhang